“The bandage is done: I washed my forehead, whose bleeding has ceased, with saltwater and put the bandages across my face. The result is not without constraints: four shirts and two tissues drenched in blood.”

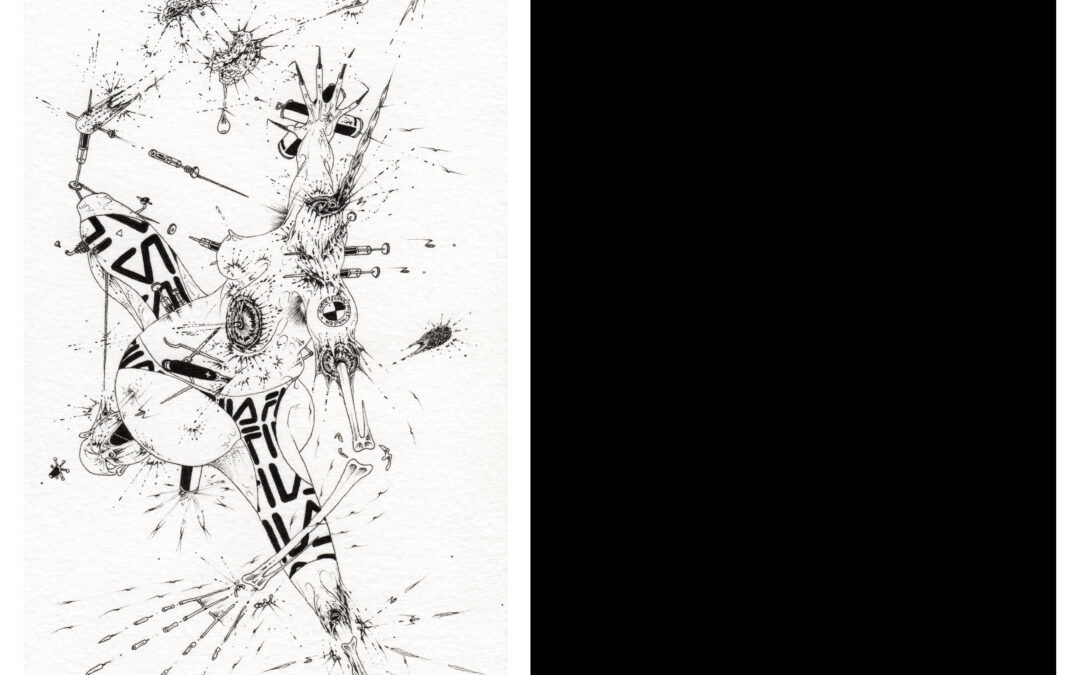

At the very beginning: splatter – torn off heads, ripped out hearts, broken off fingers and cut through penises; where ever there is a hole, a vagina, a mouth, an eye, an asshole, one can be sure that there is something sticking in it – a dick, a leg, a finger or an arm; and where there is no hole, new ones are simply pierced either with injections, needles, knifes or axes; where a rope can be tied to, for instance around the neck, the ankles or the hands, there you will find a rope that increases the tension until the limp in question breaks off or tears off, dispersing the hundreds of bitsy and splintering parts into the white pictorial space – splatter. A profanity, a dramatic art which, beyond the desperate irony, is hard to get.

The tormented bodies in these drawings are alienated – no eye is created for the purpose of sticking a dick or a finger in it, is it? Likewise, no eye is made for seeing such things. The bodies pecked with injections, perforated with needles, hacked into pieces by knifes, torn apart by axes and ropes, crushed by invisible forces, deformed, taken apart and put back together the wrong way; in short: helplessly exposed. But hidden behind and along this brutality are the most idiotic details: a video camera is not just a video camera but a Sony camera, the turntables have to be from Technics (at least), the cigarettes with which a head is larded are from Marlboro and the kitchen knife which is cutting through a leg is manufactured in Solingen, of course. These details accommodate the drawings with such a plump humor that all pathos is blown away. So far so good.

But the pictures of Ralf Ziervogel are more than just sick fantasies, skillfully unfolding themselves in the form of fine lines on white paper. They are not the result of suppressed or stifled violent fantasies, they do not arise from the abysmal depths of a standardized society no matter how much his characters may derive from a hell of violence and torture. In his larger works Ziervogels topics become more evident: the theme of coupling and uncoupling, of interlinking and dissolving, the question of how far you can go before something breaks into pieces or tears apart and also how far reality can be stretched before it bursts, dispersing all its remainders across the picture. In all his works these states are played with and highlighted from all different perspectives, interconnecting them all within themselves. However, in the world of the artist there is no layering, no overlapping of different levels. At first there is only a plain succession: one thing is followed by the next, the one by the two, the two by the three and so on. But this continuity is quickly bent, branches out and ramifies itself and finally results in a form of weird coexistence derived from different loops: suddenly the next is also followed by the first, the three by the two and the two by the one and at some point even the one by the three and the two by the other, which connects the first with the three only to backwardly push itself again into the one. That’s how one should try to imagine it – every step in itself makes perfect sense, as a whole however the result is total chaos: there is no front and no back and in contrast to the first impression no linearity, but rather a knotted meander or even a helix. On these labyrinthine passages through the swamp of his drawings, these works at some point change their status and all of a sudden they have nothing anymore to do with what they started out as. They are monsters, which can change their faces at any given moment, amorphous excrescences not much unalike a tumor in a diseased brain. Or is the brain itself the tumor? Of course, what else…

But one step back and again from the top: as one directs ones focus on the bitsy and figurative level of these pictures, there where random characters are constantly penetrated either by other characters or objects in unforeseen manners, they add up to a moving tapeworm, nourishing on a grammar of dramatics and telling poems in swinish verses filled with brute force and unvarnished sex: they always discharge in a continuous out-branching and multiplying panopticon of the perverted and obscene. On this level seeing the whole picture is of lesser importance since especially while reading, the eye has to follow the different stages from close range into the complex chaos with neither beginning nor ending.

However, as one takes a step back these interconnections dissolve – not by rapture as seen on the theme-level where arms, legs, whole bodies or tongues and heads cannot withstand the drag and tear off, but more by the contrary: the multitude of trivia and details of horror and profanity merge to one ornamental pattern, to a rampant structure, which creeping plant-like grows across the paper; or a DNA-structure, a tree house tediously constructed out of bamboo rods, or something alike. From distance the installative component of Ziervogels works becomes evident, which despite the bitsyness of his drawings is always present: His paper webs elongate themselves into the room and their effect on the viewers perception changes depending on the distance from which they are looked at – they can be read from very close range, then the dramatic details over weigh, but they can also be appreciated from the depth of the room. Then the brutality and sex of each single motive merge to one abstractinstallative composition. The question of abstraction or figuration is thus moved into the room. As what one perceives them solely depends on the point of view of the spectator. Sometimes it even appears as if Ralf Ziervogel had hidden these small obscene details in his pictures as a mean joke, which only reveals itself when one is close enough to see what is really displayed. On the second view its more of a shock, which ambushes the intrigued approach from behind when it comes closer and the first details get out of the range of perception.

Also the small format series under the name “Every Adidas got its Story” lives from this double-pairing of abysses mannerly brought to paper on the one hand, and an almost minimal installative and reduced presentation of the whole on the other. This series includes a total of one hundred works, all kept in the same format and all loaded with the common amount of sex and brutality. These drawings, which are only little larger by size than a postcard, are accompanied by a suiting black paperboard of the same format on the right hand side, presented together leaning against the wall on a small wooden shelf: Postcards from hell, ready at hand and to be posted, transform the exhibition room to an armory, from which letter bombs can be sent to the outer world. And still it all appears highly fancy, so slick and well composed – all thanks to the even distribution along the walls on which the drawings are always presented in even numbers in order to underline the equality of all works. And thus they are nevertheless united again in one big union and all individual stories melt to one collective statement, connected by the egalitarian presentation.

Thus Ziervogels works communicate, despite all the pressure, tearing and ripping, which can also be found in them, a sense of a form of “equilibrium”, which however is not resting within itself but which arises from the painstaking balancing of the forces that take effect on the paper. Here everything seems to be longing to explode or implode, often even both at the same time, but the controversial elements are nevertheless brought to a fragile balance in the end. The secret lies in the inversion of the inside to the outside, the entrails into the visual space of the picture into the room and back: Before and thereafter are merging in the picture, the inward is outward and the outward is inward. Strictly speaking neither exists since Ziervogels pictures are analogies of an embracing and complete interior of the outward, within which everything constantly changes to its contrary – here everything takes place on the same surface and an equilibrium is reached by an equal treatment of all aspects. But for that the bodies first have to tear apart and spit their bowls and guts onto the canvas so that they can be carried into a balanced compositional arrangement – similar to Louis Bunuel’s cut through the eye at the beginning of Un chien andalou, which as a dramatic inauguration makes it only now possible that the view can turn inwards, finding the well known insanity and bringing it to the surface where it can happily multiply and reproduce associatively copulating. – an equilibrium rooted in a radicalness – with a persistent urge for continuous dissolution. All tends towards zero, swallows itself, turns inwards and convulsively immediately back outwards, disappears in the asshole of the world only to be reborn out of the mouth as a half-digested negative of a slide picture. Everything is pushing to dissolve, disappear and to reappear only to disappear again: a circular equilibrium in contrast – black on white. White on black. Black on white. White on black.

“At the foot is a Grace Jones-Advertising blow-up sqaller, out of which a Buffalo shoe-wearing lesbian comes marching out, with lemon-logo-air balloons in her hand. On the balloons pumped up by CO2 bottles live thousands of spiders and insects, the whole with a miniature house and decorated with a Dagobert head. The busy crawling mass is recorded with a Sony camera and forwarded by satellite. Parallel to the right a tall Amy-Mullins-stilt stakes a DAAD-Korean with dental floss straight through his body.”

Text: Dominikus Müller, first published in „Every Adidas Got Its Story,“ 2008.

OPENING

27.04.2023

19:00 to 22:00

The opening is public.

EXHIBITION

Duration:

27.04. -11.06.2023

OPENING TIMES

by appointment